123/154

\begin{frame}

\frametitle{Infinite Limits: Definition}

\begin{center}

\scalebox{.6}{

\begin{tikzpicture}[default]

\diagram{-2}{5}{-2}{2.5}{0}

\diagramannotatez

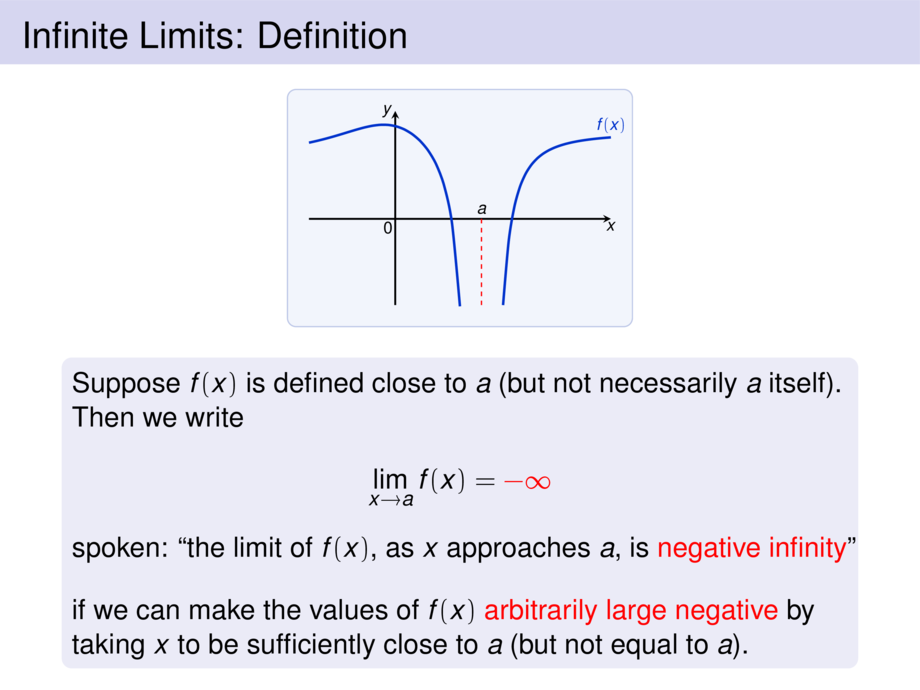

\draw[cblue,ultra thick] plot[smooth,domain=-2:1.5,samples=20] function{-(1/((x-2)**2)-3/(x**2 + 3)+0.6)+2};

\draw[cblue,ultra thick] plot[smooth,domain=2.5:5,samples=20] function{-(1/((x-2)**2)) + 2} node [above] {$f(x)$};

\node [anchor=south,inner sep=1mm] at (2cm,0cm) {$a$};

\draw [dashed,cred] (2cm,0cm) -- (2cm,-2cm);

\end{tikzpicture}

}

\end{center}

\begin{block}{}

Suppose $f(x)$ is defined close to $a$ (but not necessarily $a$ itself).

Then we write

\begin{gather*}

\lim_{x\to a} f(x) = \alert{-\infty}\\[1ex]

\text{spoken: ``the limit of $f(x)$, as $x$ approaches $a$, is \alert{negative infinity}''}

\end{gather*}

if we can make the values of $f(x)$ \alert{arbitrarily large negative}

by taking $x$ to be sufficiently close to $a$ (but not equal to $a$).

\end{block}

\vspace{10cm}

\end{frame}